The concept of the Synthesizer.

Subtractive synthesis is one of the oldest approaches to synthesizing sounds electronically. Some say it started with the Moog… but there are synthesizers of a sort that pre-date the Moog. Even the Hammond organ and the Theremin are a form of synthesizer.

The building blocks of a synthesizer.

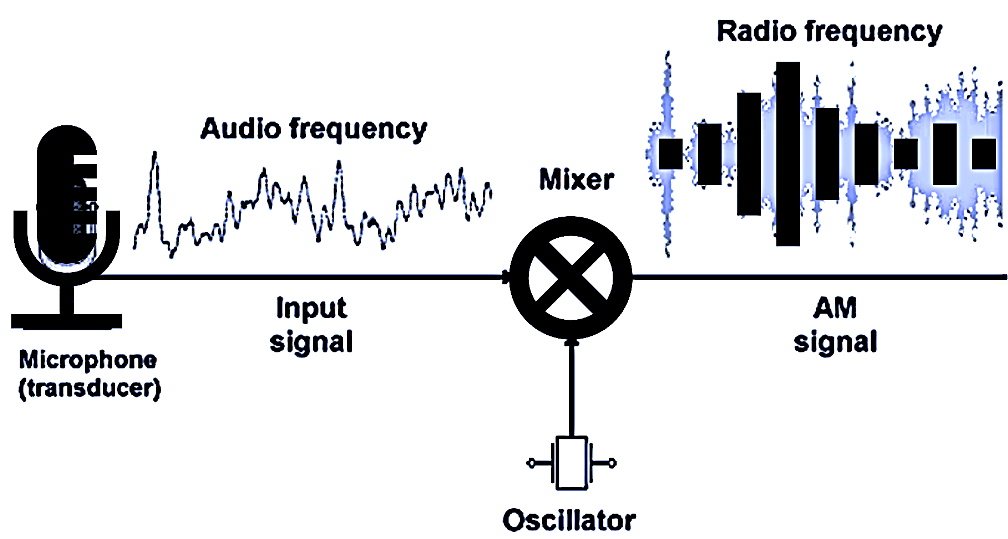

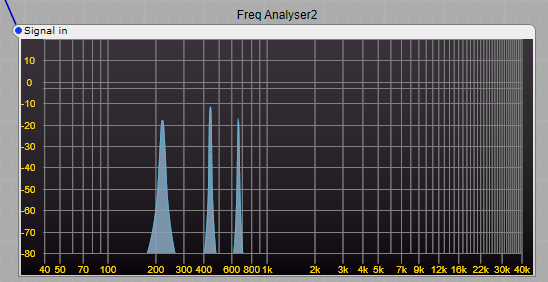

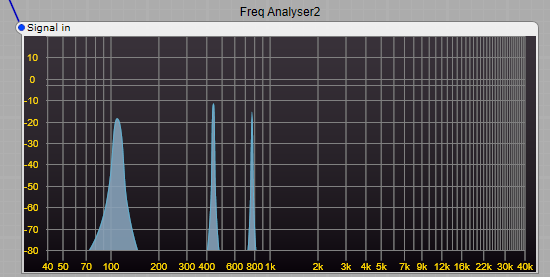

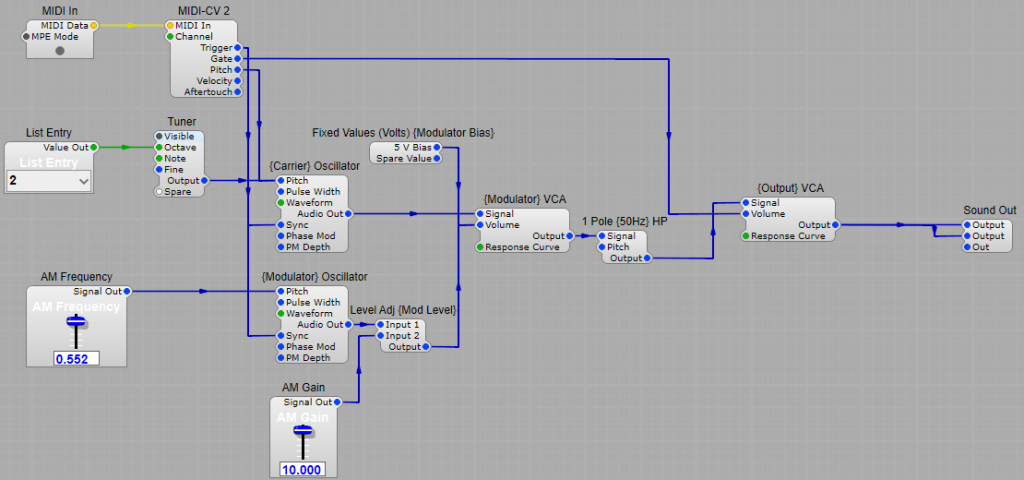

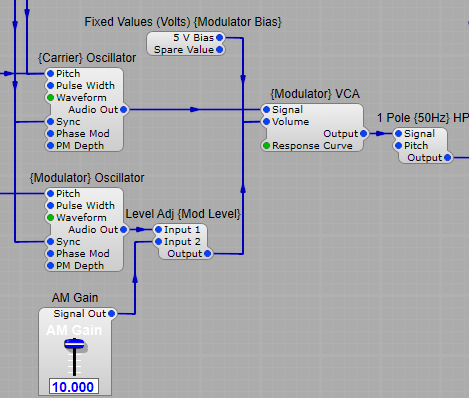

We start off with one or more voltage controlled oscillators (VCO) with a harmonically rich sound. Harmonics being the odd or even multiples of the oscillator’s frequency. Two or three oscillators can be mixed together in the mixer along with white or pink noise if required (a hissing sound).

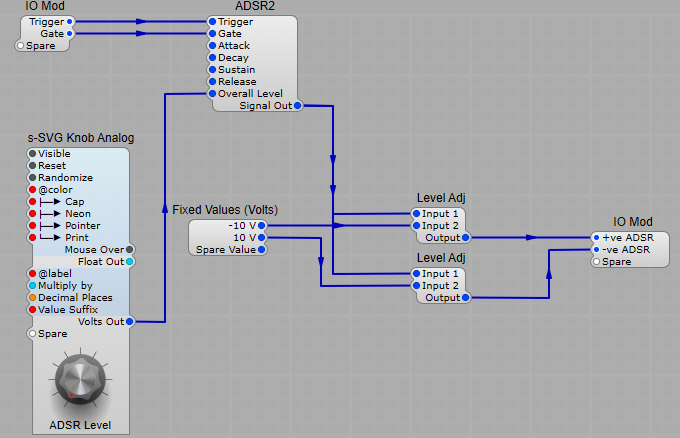

The LFO is just a lower frequency version of a VCO that can be controlled manually to produce tremolo, vibrato or filter sweep effects.

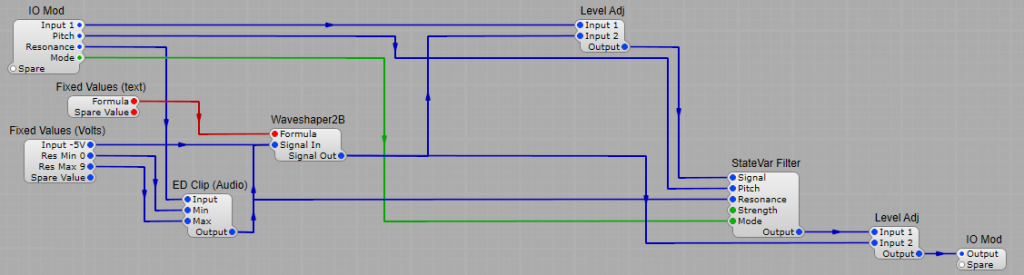

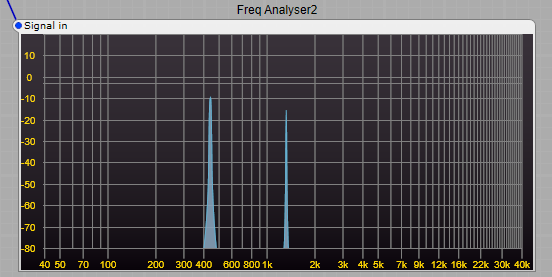

We then use a voltage controlled filter (VCF) using the resulting audio to boost and or cut certain frequencies. Various other methods of adding harmonics can be used before filtering such as wave-shapers, clippers and ring modulators (more about these later). The filters cut-off frequency can be modulated to provide some harmonic variation, followed by a voltage controlled amplifier modulated by an envelope wave form (ADSR) triggered by the keyboard. ADSR can also be used to modulate the VCF.

Using voltage control of pitch, timbre and amplitude gives so us a huge amount of flexibility and musicality in the instrument.

I’ll explain some of the key phrases here:

Voltage Controlled Oscillator (VCO)

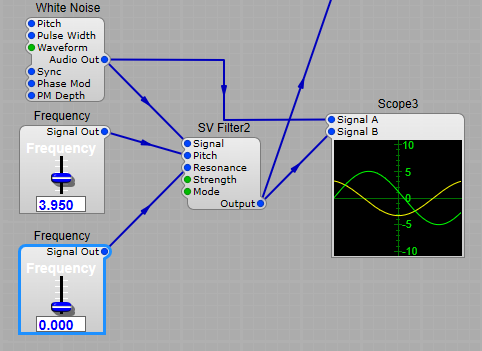

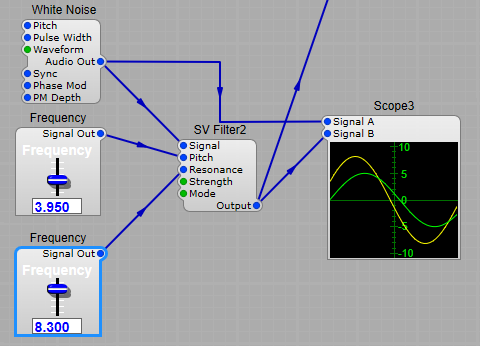

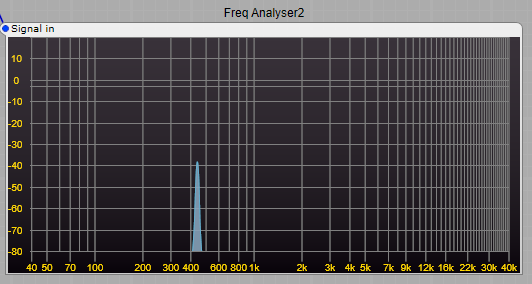

This produces our sound, the pitch of which is controlled by a voltage from the keyboard. It can be a simple pure sine wave with no harmonics, or a very rich sawtooth signal. Some of the types of waveform are shown below.

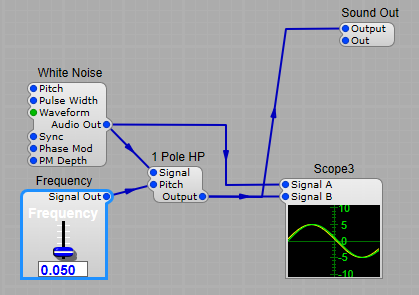

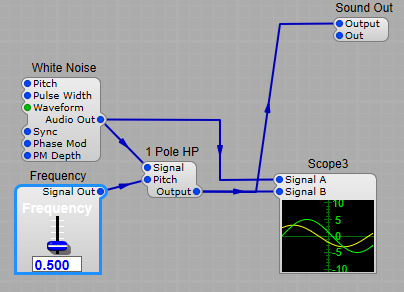

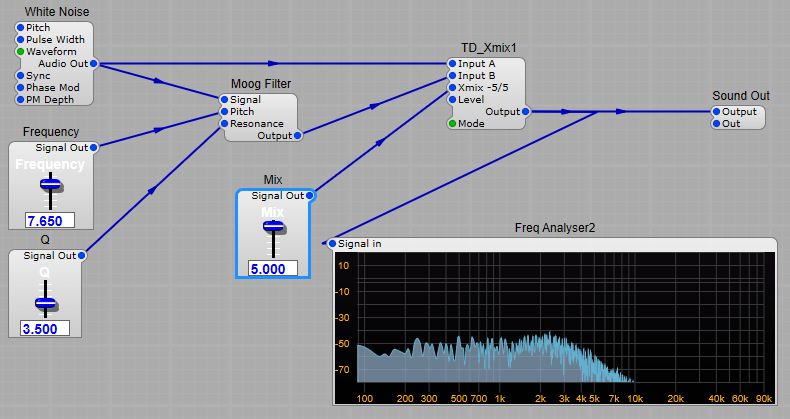

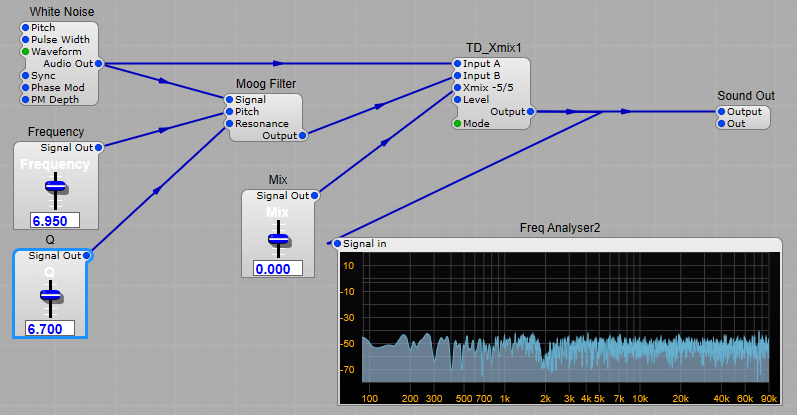

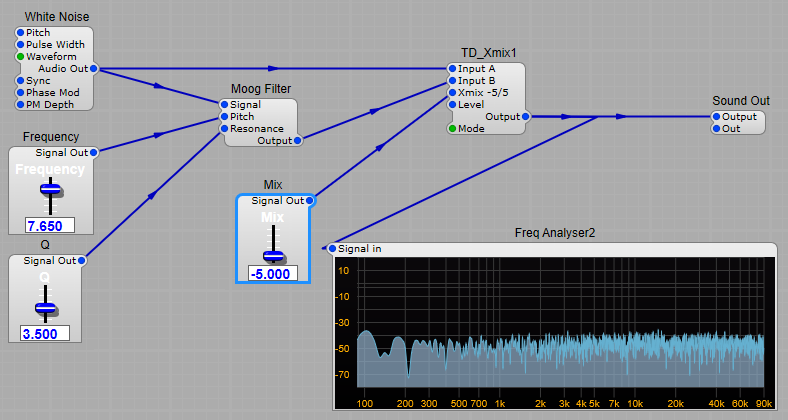

White/Pink Noise Generator, This produces a random audio signal producing a hissing noise useful for creating percussion, the sound of wind and rain, or “breath” effects for creating certain instruments.

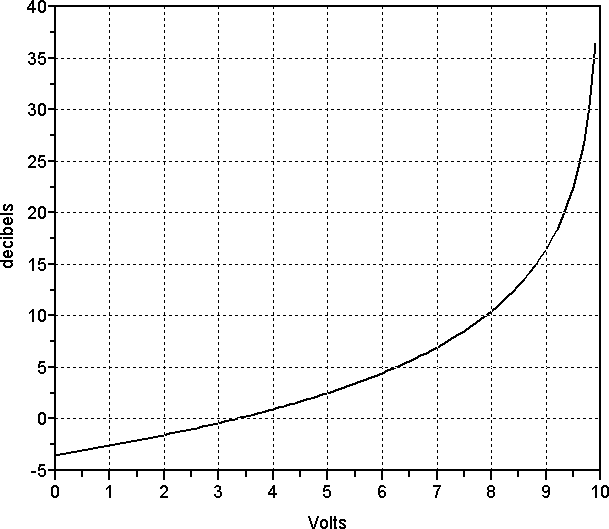

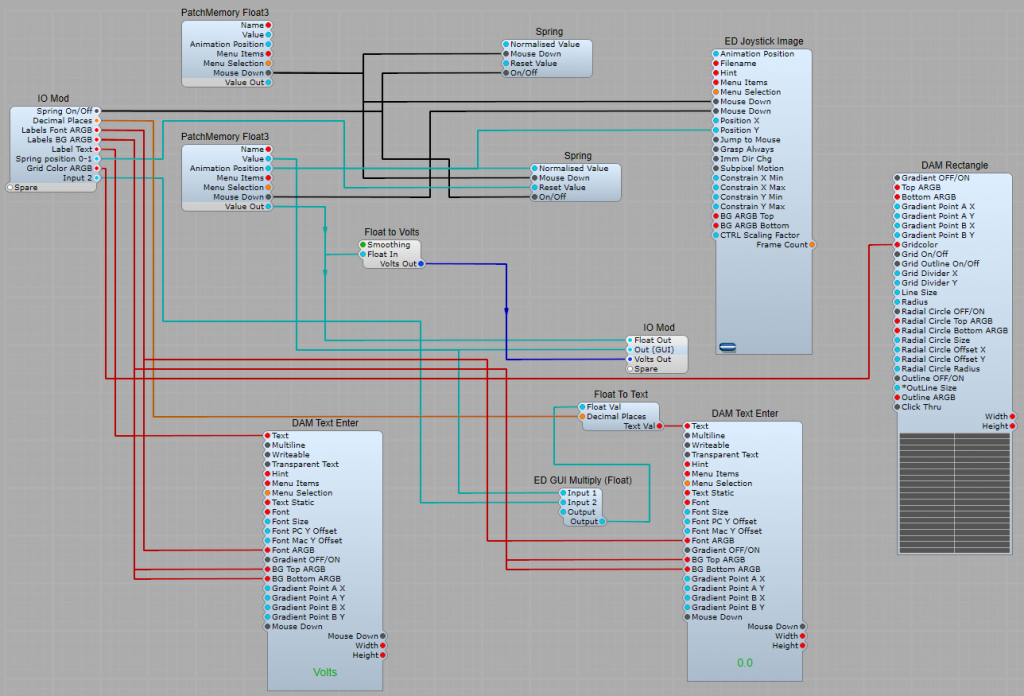

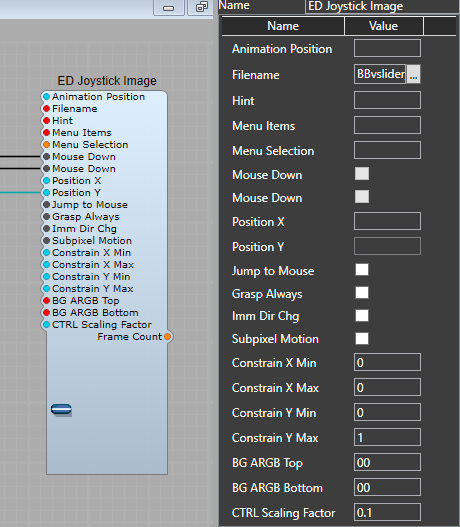

Voltage Controlled Filter (VCF), usually a low pass filter, this takes our sound from the VCO and filters it removing some of the higher frequencies from our audio. We can control the cut-off point for control over the timbre, and add some feedback to produce a more resonant sound. See the diagram below, that little peak at the cut-off frequency is where the resonance occurs. Filter cutoff frequency can be modulated using ADSRs’, LFOs’ and other control voltage generators.

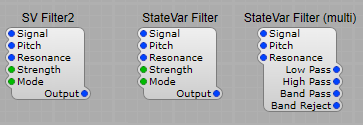

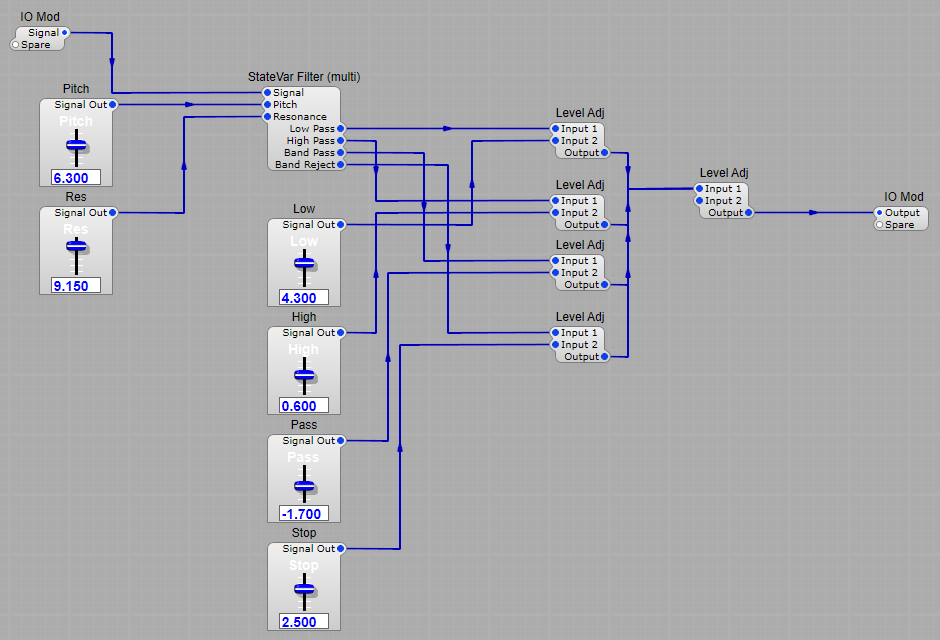

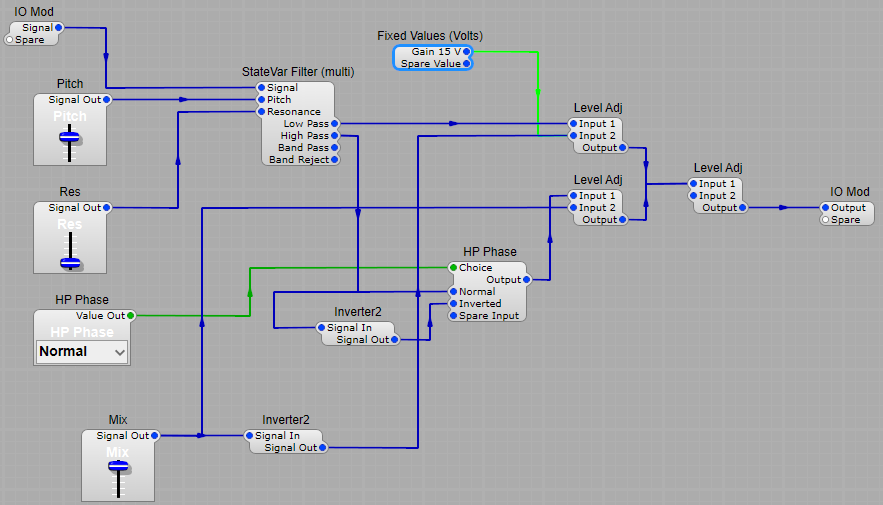

However we are by no means limited to low pass filters… there are high pass, band pass, and notch filters too… and we can combine these filter types too…

More about Filters

Controlling the volume with a VCA and an Envelope Generator.

Voltage Controlled Amplifier (VCA), this does just what it says on the tin and controls the loudness of the sound leaving our synthesizer.

It really is as simple as using a varying voltage co control the volume of the sound.

More about VCAs

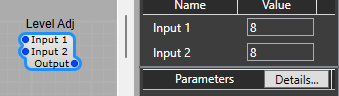

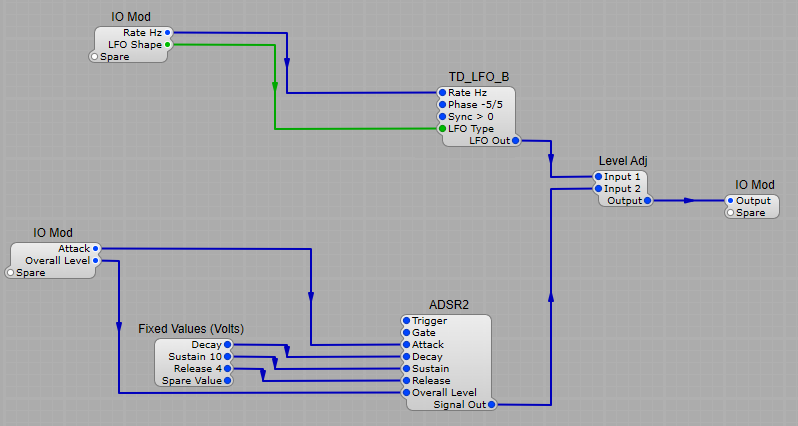

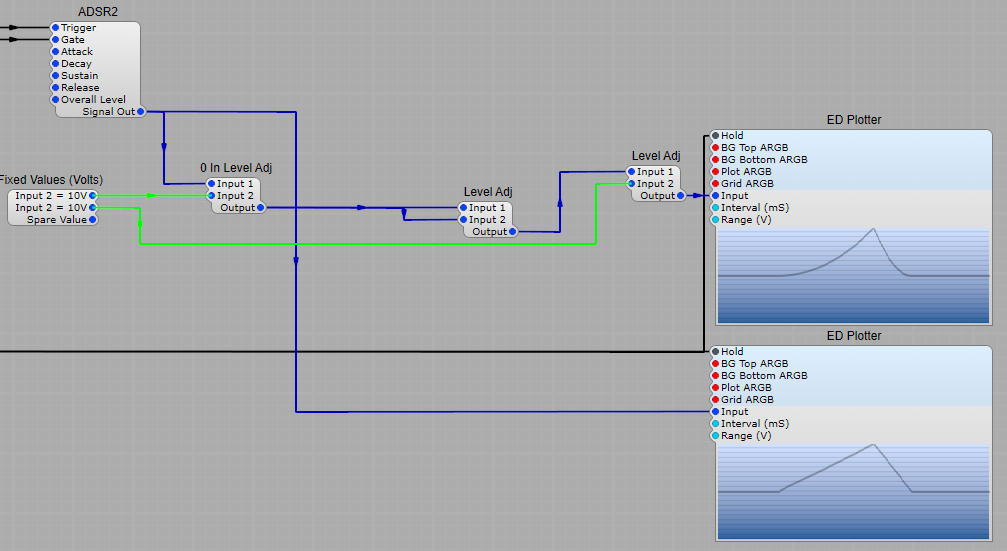

This is usually done with the Envelope Generator (EG also ADSR), OK so this might be a little confusing… why is the EG also ADSR? Well it generates a voltage which can be used to control both the VCF (sweep the cut-off frequency) and the VCA (the loudness of the audio).

Notice the shape of the envelope in the diagram below, it has four stages; 1) Attack (A), 2) Decay (D), 3) Sustain (S), Release (R).

The terms Envelope Generator and ADSR are often used interchangeably. However some early synthesizers just had Attack and Release controls, there was no decay control or control over sustain level.

More about ADSR

Getting More complex.

We are by no means limited to just these few modules. We can have as many oscillators as required, additional filtering, and other ways of altering the sounds we are generating.

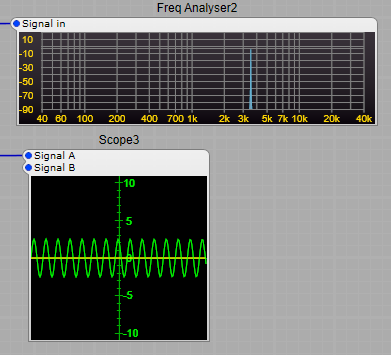

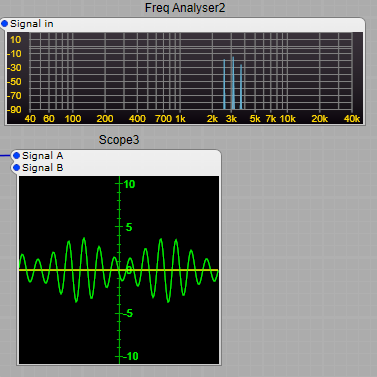

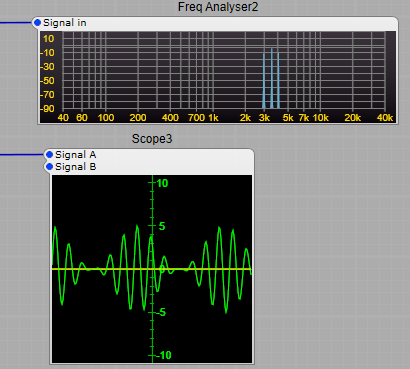

Various other methods of adding harmonics can be used before filtering such as wave-shapers, clippers and ring modulators.